decisions

The Moment of Impact

I was recently talking with a friend of mine who is an avid golfer. He loves the game, practices religiously, and is committed to bettering his skills. As we talked, he educated me a lot about the various clubs in his bag and about the essential elements of his swing. But he said one thing, in particular, that sort of stuck in my head. He said, in relation to the initial drive, that he’s seen a good number of golfers who position themselves into what appears to be a very strong drive. They have the right stance, the right arm and body position, and know how to hold the club. But, he said, for some reason, they slow their swing right at the very moment the club is set to hit the ball. That single moment of hesitation leads to a less than desired result.

I was recently talking with a friend of mine who is an avid golfer. He loves the game, practices religiously, and is committed to bettering his skills. As we talked, he educated me a lot about the various clubs in his bag and about the essential elements of his swing. But he said one thing, in particular, that sort of stuck in my head. He said, in relation to the initial drive, that he’s seen a good number of golfers who position themselves into what appears to be a very strong drive. They have the right stance, the right arm and body position, and know how to hold the club. But, he said, for some reason, they slow their swing right at the very moment the club is set to hit the ball. That single moment of hesitation leads to a less than desired result.

In golf or in any other endeavor, I am led to think about how we respond right before any critical moment; that moment when the club hits the ball, if you will. That moment is the last of its kind. After it passes – and depending on how we respond – the future is shaped. That moment of impact is a defining moment. It sets our course.

If we move off the golf course, I think we see life moments like this all the time. Anytime we’ve invested ourselves into something, there comes a moment when our commitment and follow-through are tested. Can you think of a time when you second guessed something for just a moment and lost momentum? Perhaps a quick hesitation in an answer or an action changed the course of your life? I can certainly think of more than one time where I stepped up to hit the ball – and I mean I was really ready to whack it – and then, in that critical moment, I choked.

I’m not casting any judgement on moments of hesitation. Certainly, there are times when something just doesn’t feel right. The universe sort of sends signs about a need to slow down or change course. What I am wondering about, however, are those moments of hesitation caused by fear. How often do we come fully prepared for something after giving it lots of thought or practice and then fail to deliver on our follow-through? How often do we maybe not commit to hitting that ball as hard as we could because we are afraid?

I guess that’s the “think-about.” In the critical moments, do we let fear slow us down or somehow alter our potential? Or, are we able to position ourselves to take the swing with the original impact we intended? I think the answer probably offers us something really meaningful to consider.

The Divorce that Broke the Internet

I heard on the radio today that the breakup of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie actually broke the internet. I’m not sure if that’s exactly accurate, but when I heard the report I was immediately struck by it. I mean, it would take a lot of people to actually break the internet, right?

True statement or not, I have no doubt about people’s curiosity to read the gossip. What I do wonder about, however, is their motivation for being so interested. It’s not like Brad Pitt is some hot handyman in the neighborhood and now all the single women have a shot with him (and yes, I’m assuming that most news seekers in this case are women. Terrible how I’m perpetuating a stereotype, I know). But as I think about it, I believe there are probably two reasons for people’s curiosity: people are either saddened or shocked by the celebrity breakup; or people find some kind of relief in being able to relate to it.

Relationships end all the time. We’ve all known seemingly perfect couples who have called it quits for one reason or another. After all, it is so easy to judge a relationship from the outside with statements like, “Oh, they seemed so happy,” or “They were so good together.” The truth is that we never really know the secrets of a relationship; the things that happen – or don’t happen – in private. It may even be true that in some cases, one of the people in the actual relationship is struggling to understand the breakup, not sure why the person they held closest to them decided to disengage or call it quits.

While Brad and Angelina appeared to the world to be the perfect power couple – blessed with fame and fortune, and enough love to adopt children from all over the world – the media is now in the business of citing blame for the breakup. And as more and more people speculate about what happened to cause such an upheaval, more and more reasons for the split are revealed. I guess I don’t understand why there has to be a victim; why there always has to be someone blamed. I’m stuck on the basics of the story: two people who loved each other have decided that it’s not in their best interest to be together, and in the wake of their relationship stand six children of a broken home. Celebrities or not, these are still people. This is a story full of disappointment and loss. Somewhere in the middle of “happily ever after” and divorce, I bet there was also a lot of turmoil and difficult decisions. Perhaps people pay attention to the story because what looked like a strong and good partnership turned into something very ordinary and disappointing.

In addition to those who might see the sadness in the Brangelina breakup are also those who, I think, find some comfort in it. How many of us experience a breakup and are left wondering, “What could I have done differently?” Even more often, I think people begin to question themselves, making “what if” statements about losing weight, being more patient, having more sex, etc. But to witness the breakup of a couple that was so celebrated seems to say, “Look, even Brad and Angelina aren’t perfect.” And in that statement, there’s an opportunity for all of us to be just a little kinder to ourselves. I mean if they couldn’t make it with all their money and privilege, how will we? Right?

When this story’s 15 minutes of fame are over, the truth is that there will still be a family affected. With a divorce rate in the United States somewhere around 50%, a break-up like this – along with Taylor Swift songs and country music – remind those of us who have had failed relationships that we are not alone. And once again we are reminded that while money is great to have, it can’t buy us happiness and it sure as hell doesn’t buy love.

Like a Fighter Pilot in Love…

People often say, “You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.” I’m not sure that’s always a true statement. In fact, I think some people know exactly what they have, but in the process of taking it for granted, they think they will never lose it or they don’t do the work to keep it. So … the realization at the end isn’t some deep moment of clarity and awareness. It’s more an “oh shit” feeling of “I can’t believe it’s actually gone.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about loss lately … not like losing my keys or my wallet, but the loss of people from our lives. Sometimes loss comes from death, but it also comes from changes in situation (like someone gets a job and moves across the country), or from rough patches in a relationship that just can’t be mended. Sometimes loss happens abruptly. But sometimes it happens over time as a gradual process, like helium from a balloon that sits stagnant too long, or a flower that’s gone too long without water. The relationship wilts. And without the right attention, it will die.

I was reading an article online recently about fighter pilots. In addition to all the implied dangers of the job, these pilots face an insidious threat called hypoxia. Because the system that produces oxygen for pilots who fly at high altitudes is not always perfect, pilots sometimes suffer from a lack of oxygen to their brains which can produce light-headedness or a lack of concentration (like the symptoms we may more commonly associate with high-altitude mountain climbers). In worst case scenarios, a pilot can black out from the lack of oxygen. Unless he “wakes up,” he could end up descending hopelessly into the ocean.

So what does this have to do with relationships? I think the slow, gradual loss of a relationship is a lot like hypoxia. Something happens that causes our relationship to stop breathing. And unless we can find a way to once again start sucking oxygen into it, we find ourselves disoriented and disconnected. Our relationship becomes distressed.

And so I go back to my opening observation. I wonder how often people in distressed relationships actually stop to think about what they have – and if what they have (maybe not at the moment, but overall) makes them happy. Unlike the pilot who may not even be aware of his impairment, partners in a hypoxic relationship could work together to breathe new life into their situation. Of course, there is also a chance to pull the metaphorical parachute and escape. Either way is a choice. And both choices, I believe, are ok ….as long as we made the effort to know and value what we had before it was gone.

Seeking Joy

I was watching a TV hospital drama the other night. One of the patients came into the emergency room after being hit by a car. He said that he was texting and walked right into the street without even noticing the car that subsequently struck him. Luckily, the man sustained only minor injuries to his lower leg. But over the course of treatment, the head of psychiatry noticed the man’s underlying depression. He asked the man if he stepped intentionally in front of the car. After some prodding, the man admitted that he had. He said, “I have the perfect life, the perfect marriage, the perfect job. I have nothing to be sad about. And yet, I am sad all the time. Nothing makes me happy.”

I continue to think about this episode because it made me wonder how many of us are silently struggling with fears and insecurities and doubts that we do not discuss. How does our notion of “perfect” put pressure on us? Moreover, how does what others call perfect guilt us into thinking that we should be happy and make us feel inadequate when we are not? Are we even able to define happiness for ourselves anymore? And most importantly, do we think we deserve to be happy?

I believe that there are very few people in the world who live a joyous life. Maybe I’m wrong. But my opinion is that people settle, and in that settlement they find comfort. Comfort and joy, however, are two very different things. One can live a comfortable life – and become comfortably numb in the process – without ever knowing joy. I would argue, however, that the greatest life is one that is both comfortable and joyous. And joy comes from living life as your authentic self.

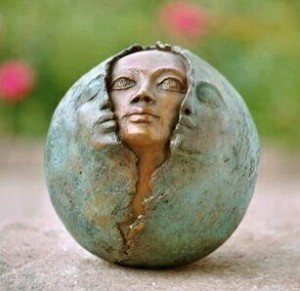

Many years ago, I read a book by Dr. Phil called “Self Matters.” In that book, Dr. Phil defines the authentic self as “who you were created to be.” He also refers to the fictional self, which is “who the world has told you to be.” He explains that when people are asked who they are, they often answer with a role they play or a place they come from (mom, husband, lawyer, Penn Stater, etc.). Different from these answers, however, is a deeper response to the question, “Who are you?”. He states that this deeper response is found in the authentic self; it is found at your core and is not defined by your job, function or role. “It is all of the things that are uniquely yours and need expression, rather than what you believe you are supposed to be and do.”

I think the world is really good at helping us to create our fictional selves. It is easy to listen to outside influences, pay attention to everyone else’s expectations, and fall victim to someone else’s definition of what happy looks like. It is much harder to think beyond convention and listen to our inner self. After all, what if that little voice inside of me is wrong? What if I step off the beaten path and end up lost and alone in the woods? Then what?

Last August, I posted “Walking the Path.” It was then that I wrote: “The path forward can sometimes become unclear, possibly grown over with brush, or disrupted by broken cobblestones. When this break in the path happens, it is easy for us to retreat; to turn and go back from where we came. And I guess that’s sometimes ok. The places we have already been are known to us; even when they are not exactly pleasant, we know we can survive these places because we’ve already lived in them. We know what the expectations in those places are; we know how people will treat us and what will be the norm.”

As I reread that now, I am thinking about the path in a different way. Perhaps the breaks in our path are opportunities for us to consider the life we are living; to evaluate whether or not we are honoring our authentic selves. And perhaps if the path feels broken or challenging, it is not because we are being called to retreat, but that our authentic self is pushing us forward and calling us to break from the fictional self we’ve allowed the path to create for us in the first place. We might sacrifice comfort for a short time as we grow and evolve, but the resulting joy? I bet that’s worth it.

I’ll Have the Lobster … Maybe

Indecision is a cruel thing to suffer. It could be as simple as choosing a menu item or the color of a tie. We go back and forth and back and forth, weighing the attributes of each choice. This flow of thought becomes ridiculously maddening. Imagine how that struggle deepens when indecision carries over from something as simple as dinner to something as complicated as relationships.

I, myself, have been in many situations where a choice was a difficult thing to make. In some cases, I was able to prolong my indifference in a way that the choice was just eventually made for me. But I have to admit, I’m not a big fan of having choices made FOR me. Instead, I prefer to maintain control. I prefer to decide. And so, what do we do about indecision?

Reasons for indecision are varied, but I believe people have the most difficulty when they walk the line between what they feel obligated to do and what they want to do. Moreover, indecision often lies not in the true value of each choice, but in the value we place (deservingly or not) on what is easy or comfortable. As humans, we don’t always like to stretch – our palates, our minds, our hearts. And so the “comfort zone” is an easy place where the decisions we’ve made in the past live. These are the foods, vacation spots, job opportunities, and even people that we’ve already tried on for size. And in the process of that trial, we’ve deemed them safe (or at least tolerable). The risk in committing to something new is that we have to learn all over again whether or not we like that something. And, if we don’t, we have to be able to embrace the decision as a learning process, not as a regret.

I think every reader knows exactly what I mean. To put it in simple terms, consider that one restaurant; the place where you always order the same exact thing off the menu. We all have that place. And we all do the same thing. We look at the menu, we see some things that look delicious, we struggle to make a decision, and then we pick the same old thing. Why? The answer is not simply that we know that dish is good. It is also because we’re afraid we’ll be disappointed if we pick something new and it just isn’t as tasty as our regular meal. We are afraid of the potential regret.

Decision-making is hard. When presented with two (or more) choices, making a decision means that we take a risk on one thing over the others. It means that some things fall off to the side. In that way, we have to not only be comfortable with deciding, we also have to be ok with letting some things go. And letting things go is even harder.

And so, what do we do? I read a very interesting article recently called “Resolving Indecision” where the author differentiates very clearly about choices and decisions. He says:

“To address indecision, I’d like to first make a distinction between decisions and choices, because I think people get themselves into trouble conflating the two. I think that it is best to think of choices as preferences that stem from subjective personal tastes. A decision, on the other hand, is a commitment to action that occurs after one becomes aware of their choice. For example, yesterday I chose between Snickers and M&M’s, and upon realizing that I wasn’t in the mood for caramel I made the decision to buy the M&M’s. Choices are often difficult, but I suspect that most of the time people lean at least slightly one way or the other, and that if push came to shove they could state a preference.”

And so, maybe the struggle lies not in the decision (which is the implementation of choice), but in actually knowing ourselves well enough to distinguish our preferences. What is challenging is to think about these preferences outside of anything else – free from obligation, free from familiarity, free from a fear of regret. Do we really know what we like? Can we identify the things that make us not just content, but truly happy? Most importantly, do we believe we deserve that happiness? I suspect that answering those questions is where the real work lies. Any decision after that is a piece of cake.